- Kevin Deegan-Krause, Wayne State University

- Tim Haughton, University of Birmingham

- Ján Rovny, Sciences Po

- Stephen Whitefield, Oxford University

This is a full text of a discussion that appears in abbreviated version on the SSEES Research Blog of the UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies (http://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/ssees/2015/01/19/all-tomorrows-parties-the-future/).

The editors of East European Politics and Societies are grateful to the SSEES Research Blog for hosting this discussion. EEPS is at home at SSEES. Not only is the journal co-edited there, but SSEES and EEPS play complementary roles in supporting and promoting the best in East European studies.

–Wendy Bracewell (SSEES) and Krzysztof Jasiewicz (Washington and Lee University), Editors, EEPS

A few words of introduction: This discussion had its birth in the “Whither Eastern Europe” conference held at the University of Florida in January 2014 which sparked a series of conversation, both during the presentations and during the excellent breakfasts, lunches and dinners that surrounded the formal sessions. When East European Politics and Societies and Cultures inquired about the possibility of publishing several papers in a special issue, the authors offered to work together to produce this supplementary work to reflect the discussions that were so productive toward building a consensus (and revealing differences). The conversation presented here comprises a combination of in-person conversations, online-text conversations and text responses to a formal set of questions with the goal of coming to greater understanding of what we know about political parties in Eastern Europe, what we still need to learn, and how we can get there.

–Kevin Deegan-Krause, Wayne State University

Dimensions of Competition

Deegan-Krause: Let’s start with a simple question: Is there anything we know we can agree about?

Whitefield: I found it highly instructive to ponder the lessons from three intertwined perspectives. First, what do citizens want from parties? Second, what do parties have to offer to citizens? Third, how does the communication between parties and voters help deliver good democratic governance?

In terms of the citizen-party relationship, I believe that Robert Rohrschneider and I have already well-established that the underlying cleavage structure at the party-level differs between East and West: largely one-dimensional in the East but – importantly – no sign as yet of a shift in the axis of the dimension to resemble the West: in the East, party competition is still based on pro-West/Europe, pro-market, pro-democratic parties versus their opposite.

Rovny: Depending on country circumstances and legacies, you should find different combinations of the left-right versus gal-tan and different degrees of salience. The key is ethnicity (and state-building).

Whitefield: Of course, there is local variation. In some countries – historical national boundaries in Hungary for example or ethnic divisions in Ukraine or Latvia – specific issues are present that give national distinctiveness to party competition. But nonetheless, there exists powerful evidence of the importance of a Communist legacy on the nature of cleavages in the region as a whole and even of the freezing of the party systems there.

Underlying structures

Deegan-Krause: To the extent we do see programmatic patterns (or other patterns for that matter), where do they come from? Do you see them anchored in the experiences of the region and if so, which ones?

Rovny: One of the most interesting debates has been the one on structure versus volatility of politics in eastern Europe. It seems to me that this debate has by now found a set of generally accepted conclusions. First, the literature on party systems and voting behavior clearly and continuously finds increased levels of organizational volatility — parties get born, merged and dissolved more frequently than in the west — as well as increased levels of voting volatility — voters switch between parties at a higher rate than in the west, while fewer people turn out to vote. At the same time, the literature on ideological structure continuously concludes that parties in the region offer reasonably framed ideological choices, and voters select parties on the basis of their political preferences. Strikingly, these two conclusions are seemingly contradictory: organizational and electoral volatility contrasts ideological structure. I believe that we should aim at the theoretical reconciliation of these findings by accepting that structured stability and volatility can coexist.

Deegan-Krause: Let’s talk about stability first. Given the kinds of electoral results we see in the region, it is interesting that there is any talk about stability at all.

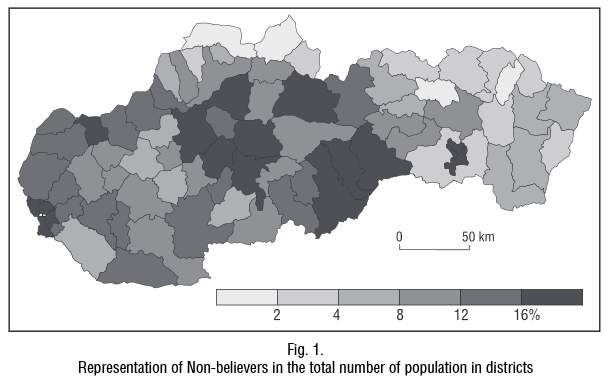

Whitefield: We agree with what Jan is saying. Work that I did with Geoff Evans in the 1990s and 2000s did indeed point to the importance (contra some expectations) of most of the usual demographic suspects. Social class, measured using the Goldthorpe-Eriksson class schema—which is really based on characteristics of occupations, particularly manual/non-manual and the supervised/supervisory distinctions—was surprisingly useful in the post-Communist context. Given what might have happened to the nature of occupational structures, this class scheme appears both internally valid (occupation is appropriately associated with occupational characteristics in both West and East) but it also provides good predictive value to both attitudes and political behaviour, as much as in the West. As in the West, it doesn’t work as well in all countries—the cleavage structure and what parties offer helps explain variance—but it works. Age and education also work in wholly expected ways. Gender differentiates little. But where some of the most interesting results come, in my view, are from the comparative study of the impact of religion and religiosity in the region. At the extremes, Catholicism and in Catholic countries church attendance matter significantly to public political values and behaviour; in Orthodox countries, religion appears to matter little. I am intrigued to know whether this is a dog that continues not to bark in Russia and Ukraine.

Historical Legacies

Deegan-Krause: If there are deeply rooted competition patterns in the region, where do they come from? And why aren’t they more obvious in the day-to-day politics.

Rovny: Let me take the first of those two questions. Although there has been significant focus on the role of various historical legacies on the partisan divides in the region, I feel that more work needs to be done. In this regard I am an unashamed Lipset-Rokkanian. I think we can profitably apply Lipset and Rokkan in the east and I believe more effort and resources should be spent on exploring the historical, pre-communist, bases of political competition in the region. Despite its particularities, eastern Europe has been exposed to many of the same core formative historical forces, theorized and demonstrated as crucial for the west, such as the Reformation, center-periphery divides, and industrialization. State-building, its elites and the core conflicts between them in the past are crucial to what we see today. The usual suspects—conflicts over economics, religion, ethnicity—all pop up with predictable regularity, and I suspect that, as in the west, the varying exposure and response to these and similar factors is likely a fundamental source of political conflict in the region, though of course not the only one.

In this context, it seems that we, as a discipline, may have overestimated the effect of communism on the region. While communist rule certainly had significant impact on the societies and polities under study, its effect is varied, and possibly diminishing with time. When I want to be provocative, I argue that communism was a cul-de-sac for eastern Europe. A foreign imposed, post-war temporality, and I think Kitschelt makes a good point when he says that even communist regime types were determined by pre-communist legacies

Haughton: The older legacies have played an important role, though we often see them through the filter of communist legacies which often overshadowed them and sometimes reshaped them. The deepest legacy is ethnicity—the key legacy was the demographic legacy of empire. This still shapes politics in many countries in CEE and will do for years to come. In terms of the communist legacies, they matter, but increasingly in different and less direct ways. I wrote an article once where I talked about the past’s role in the ‘battlefields, uniforms and ammunition’ of party political conflict. Although lustration is still, perhaps surprisingly, an important theme to be used in the ammunition of political debate, who did what to whom is far less significant in politics today a quarter of a century on. Where communist legacies still do matter are in the terrain of politics. Communism bequeathed social and economic legacies that have shaped the ground on which party politics is conducted and how political actors think about conducting and resolving such conflicts. Nonetheless, there are not simple straight lines to draw from the communist experience to today, the impact of the communist experience is mediated through the experiences of the post-communist period (which now amounts to over half the entire communist experience in Central and Eastern Europe).

Deegan-Krause: Does communism, and the place of one’s self or one’s family in the communist system or something like that then become another sort of long term structural variable that affects the east rather than the west, a regionally-specific variant of Lipset and Rokkan’s list of cleavages? Or do we need to think about it in some other way?

Whitefield: Let me weigh in here with an example from work that Robert and I have done followed up by some work by Paul Chaisty and myself, there are dogs that continue not to bark. For example, there is the curious ongoing absence of any real association of environmental or Green politics in the East with other political issues or with the left-right dimension, while at the same time the environment does not emerge as an important political division in its own right. It appears to remain largely disconnected from what most parties stake themselves on – though there is some evidence I am looking at now that does indicate that Green parties in the East take stances and make them salient on the environment that are quite ‘normal’ in the West. Why is this? Why should it be that post-Communist citizens not only are less supportive of environmentalism than people in the West or the developing South, but are distinct from them in the way in which they ‘process’ environmental issues into the rest of their political attitudes? This after now a number of years of ‘Europeanisation’ of environmental issues in law and institutions. Of course, there are features of the transition process that are shared across the region, but if variation in experience is increasingly the order of the day, why would it be that on issues like the environment the region as a whole remains distinct. I think the best explanation has to do with the stickiness of political culture at the mass level, which is supported by something like freezing at the party level. Now, we know from West European politics since the 1960s and perhaps the contemporary scene that eventually political change comes and I am sure it will in the East. But so far, the Communist legacy remains vital to understanding the region. What was it about Communism that made its influence so lasting? That’s a complicated discussion.

Haughton: There is some nascent agreement that most voters have certain structural tendencies that push their voting in certain directions, that there is a certain stability of voter attitudes and relationships to “sides”, but at the same time voters are not always certain who exactly to vote for because there is a high degree of institutional volatility, both in the choices on offer and in the likelihood of dissatisfied voters to jump to another party on their “side”.

Volatility

Whitefield: I suppose one of the most pressing and contested questions arise from the character of party organization in the region. We know and can agree that many parties come and go, that the choices available to voters have shifted dramatically in some cases between elections, and that the organizational characteristics or parties in the East are often quite different from the classical mass party organization found in the West. I wonder what difference this makes to important political outcomes – to the nature of cleavages and to democratic representation. Richard Rose famously referred to ‘floating parties’ in a quite derogatory way, since he thought that voters would be unable to hold parties accountable from election to election. There are a number of assumptions about party behavior in Europe that presume institutionalization and programmatic consistency across parties — often on a single ideological dimension. One such issue is that that parties may not have a programmatic identity that is shared between voters’ perceptions, their electoral organizations, their candidates and their office-holders.

Rovny: Under all the institutional instability there is a structure in placements of parties in (some) ideological space. (The parties may differ, but they come and go in similar places) (the various liberals in the Czech Republic are a very good example): and yes, I think voters vote for similar type parties, though again, their names and organizations come and go

Haughton: Likewise the amazing thing about Slovakia is that we see the “right” for example with an incredibly stable share of the vote even though the menu of parties is updated for every election.

Whitefield: I agree entirely that party organization and party volatility are vital areas of study in the region. There is research – for example, Alison Smith’s work on incentives driving parties to build mass membership – that show that there are trends towards the establishment of more stable organizational party bases. But two points I think need to be made even in conditions of organizational weakness. First, as Jan Rovny has shown in a very interesting recent paper and as I have argued even about the Russian party system in the 1990s, voter-party ideological alignment is quite possible – in fact, it appears to happen – even in conditions of rapidly shifting party supply. I think this is a consequence of the rather simple one dimensional ideological structure of political cleavages. Parties can come and go, but the new ones end up competing on the same axis of division. Parties present themselves in those terms and voters are primed to recognize where parties stand. Second, Robert Rohrschneider and I noted what we called ‘a paradox of equal congruence’ in our recent book. What we found was that parties and their various voters were more or less equally aligned ideologically in the East and West. Part of this, we argued, was the result of the very simple nature of cleavages in the East, which made it easier for voters to locate parties, even new ones, while in the West voters were faced with a much more complex and multidimensional cleavage structure, which raises the bar for ideological alignment. But why were voters not more incongruent with parties in the West? Here is where the organizational factor comes into play, because in the West parties can draw on strong mass party ties and resources which significantly enhanced their capacities to represent all sorts of voters. These are largely absent in the East, so post-Communist parties can’t yet draw on organizational strengths. This is just one of a number of ways in which Robert and I are finding organizational factors in the East to work quite differently. There is a lot more mileage in that line of research to my mind.

Deegan-Krause: We are trying to understand what seems to be a change in the way parties operate, shifting toward a much more fluid environment, though one which still has significant islands of stability. Toward that end we are interested the balance between legacies (some regionally specific) and pervasive newer developments related to technology, media, and finance. There is evidence that are seeing a global shift in how electoral political institutions organize themselves and relate to voters, a shift that is related closely to new communications technology, especially the dramatic lowering of the cost of people to coordinate across distances (a reduction in relational transaction costs that discourages short-run investment in traditional organizations) and the increase in the role of individual celebrity and visibility accompanied by the success of startup models, and a further aging of generations of “members”. This has hit every field that deals with large-scale information transfer and organized persuasion, from advertising and journalism to education to political parties. There is a lot of justified talk about the role of legacies in postcommunist Europe, but the biggest may simply be that the timing of the transition meant that these changes hit when the parties in this system were new or relatively young and therefore vulnerable. Combine established but sometimes vulnerable older parties and new parties that are not built (in some cases not even designed) to survive for very long, and you get the kind of institutional instability that we see in the region. This bifurcation of the old and stable and the young and fragile creates two separate party worlds.

Rovny: The key weakness is party organization. It seems that voters often vote for parties that represent who they are or want to be in some way: this is difficult in the organizationally fluid state of EU politics

Deegan-Krause: It is interesting is that none of these parties seem like they can last and yet people vote for them. Do they look completely fragile to ordinary voters?

Haughton: Don’t underestimate how disillusioned ordinary voters have become in CEE and indeed in Western Europe. Desperate times call for desperate measures. How often do we get a sense from ordinary voters that they have confidence in any elected politician? It’s very rare. They want their lives and the life-chances of their families to be better, so they take a chance on an investigative journalist (“he seems nice and cares about corruption”) or on a local billionaire (“he’s rich so maybe he can make me rich too”). And of course the new parties never point out that they are trying to replace previous “new” parties. They’re usually careful to assign the last lot of new parties to the bad old camp.

Deegan-Krause: There does seem to a shortening of the time horizons of political leaders (and their backers) and a preference for immediate return on party investment. These differences should affect basic elements of what we can expect parties to do, from positioning themselves electorally, to choosing coalition partners, to organizing legislatures. This is happening in the West, too. Maybe not as much. We seem to have 2 theories about why this is happening in the east first they are not necessarily contradictory but 1) says that there are legacies in the east that cause this to happen, i.e. communism, weaker civil society, more economic dissatisfaction 2) (ours) says that even if 1) weren’t the case, there would be something like this because /general/ trends (weaker organization, media, the triumph of celebrity) tend to press against institutional frameworks (Naim’s The End of Power) and that E. European parties are simply easier to push over than western ones. Is there any way to decide between these and/or merge them?

Rovny: Yes, I agree when we look at the “instability” part of the equation, the cul-de-sac frustration of communism plays an important role, but the general trends are really crucial — the wind is blowing, and the CEE parties have shabby roofs. In that sense it’s not what the west is now but what the west could become.

Haughton: Most new parties don’t build their structures well enough. It’s all done too quickly—like cowboy builders—so they are vulnerable when the storms come (which they do quite often)

Deegan-Krause: It sounds as if there is not as much contradiction between the two positions as we might expect.

Haughton: Eastern European parties are fragile both because of historical and communist legacies left them with “shabby roofs” and because they (like parties everywhere) are being blown about by winds that make it difficult to tie anything down? In more concrete terms, historical legacies provide an underlying social structure which has ties to particular ideologies, but political organization and voter affinity is hindered by communism’s damage to political trust and efficacy and by new-style organizational flexibility that tends, in the absence of many really solid parties, to play a big role on the political scene. So these systems tend to replicate stable competition patterns but the parties in them come and go.

Rovny: Yes, but all countries have legacies that may cause such shabbiness, even old democracies (I am struck by this in France on a regular basis): established French parties are definitely getting rained on. And in the east it is even harder: can you build parties properly if there is no history of doing it?

Deegan-Krause: The literature on party institutionalization raises the underlying questions of whether things will actually institutionalize at all or whether that institutionalization will look like we expect it to. If it does not, what are the consequences for democracy? What are the future prospects for this kind of interaction? It is certainly different than what was hoped for in the region but should we be worried? Are its consequences mitigated by the underlying structural stability? Is there anything we can do? These are questions that will take time and effort to answer, and they will require a great deal of intra-regional and cross-regional comparison.

East and West

Deegan-Krause: The tension between uniquely communist legacies on one hand and more universal influences on the other—both pre-communist structural legacies and post-communist changes in organization and communication—raises the constant questions about the similarities and differences between Eastern European parties and those parties in the west that tend to be their reference points. How should we think about the differences between east and west.

Whitefield: In fact, what I think is remarkable about the broad range of evidence about the salience that parties attach to the positions they adopt in CEE countries is how far they correspond to MOST but not all of our expectations from the study of salience in the West. First, the right kind of parties make salient the policies that we would expect given our sense of who owns what issues. Second, and Jan has shown this in some work on the West, positional explains a large amount of salience variance and the relationship is strongly curvilinear on almost all issue dimensions – parties at the extreme on an issue make them more salient. There are some notable and interesting apparent exception

Whitefield: only democratic parties seem to make democracy salient; and only Green parties seem to make the environment strongly salient. Another difference I think I am seeing between East and West, the impact of party family in the East essentially disappears when positional differences are taken into account. In short, it isn’t that party family is not associated with position in the East, it is just that it doesn’t do any work over and above what position does: that is not the case in the West, and I am not too surprised by that since party family strikes me as a more powerfully rooted determinant of parties’ reputation and therefore stances than in the East.

Rovny: It is clear that many distinctions commonly made between eastern and western Europe are of limited utility. In various political indicators of interest such as the extent of competition over economic versus non-economic issues, there may be more variance within the two blocks than between them.

Haughton: Yes, and we need to deal with the fact that most work on political parties is still dominated by the study of Western Europe. We still tend to test theories and apply models derived from the West. (The only exception is when we revert back to using “legacies” as the core of an explanation which is increasingly unsatisfactory not least given the quarter century of developments since 1989.) It seems to us that the study of CEE should increasingly be thought of as a generator of new theories rather than just a new set of cases to apply theory from the west. At the very least we need to encourage that CEE party systems are put on a par and treated equally. This has been done by some scholars, Robert and Stephen’s book springs immediately to mind, but we need more of this.

Deegan-Krause: So what role does scholarship on Eastern Europe have to play in the broader debate in the field?

Rovny: In many ways Eastern Europe is an advanced laboratory for studying phenomena that are also affecting older democracies, such as the disestablishment of political organization and shifts in party competition.

Deegan-Krause: Yes, Eastern Europe gives us an excellent set of cases for studying what happens when new forces encounter weak parties. We see the same instability in certain places in older democracies—Italy, Israel, and Greece in a big way, and Netherlands and Belgium in a smaller way and many other countries in the West to a limited extent. Crises in many of the Mediterranean parities has not only produced volatility but has produced volatility to new kinds of parties that are themselves not built to last. The gift of the east (and much of the rest of the world) to the west, therefore, is the ability to think about how party systems change when they are not protected by “old growth” forests of established parties and what might happen when, either all at once or piece by piece, the established parties fall and are replaced by parties that look like ferns or mushrooms rather than oaks.

Haughton: We second Jan’s point about Eastern Europe being a laboratory. We think that the effects of post-transition legacies on forming governing and voting coalitions make studying Eastern Europe relevant to other areas in the world. The matter of legacies is an example of the broader phenomenon of contexts where incentives exist to use political institutions and parties for purposes other than ideological or policy-based representation. We see the region as an excellent place for studying how parties adapt to formal and informal institutions. The variation in levels of institutionalization among parties within the same system allows us to see how parties can differ in how they interact with the same institutions. The result is that we see a wider range of situations than Western Europe allows, such parties as with very low ideological cohesion and or facing imminent collapse in support.

Rovny: There are also other interesting ‘experiments’ going on in the eastern lab, and surprisingly they are ones that pertain to ideology. The east is been a testing ground for populist ideological frames connecting socially conservative and economically left-leaning positions, combined not only by some post-communist left parties, but also by most radical ‘right’ parties in the east (which are in economic terms anything but pro-market). But this is no longer just an Eastern European phenomenon. While initially unparalleled in the west, some ten years ago Herbert Kitschelt suggested that western ideological politics, depicted in two-dimensional (economic and social-cultural) space, is rotating. Western parties are less divided over economic issues and more over social cultural issues as the left becomes more economically centrist and the right becomes more socially conservative. Given the latest developments in radical ‘right’ positions in the west, which are slowly taking more economically left-leaning stances (the French FN is the best example), we may see a reproduction of eastern patterns of party competition in the west. Additionally, my recent work suggests an intimate ideological connection between ethnic minorities, their views about civil liberties, and general ideological outlooks of parties associated with them — a relationship which I argue significantly co-shaped party competition in the east. It may also come as some surprise but it may be that the differences between East and West are smaller than they seem, even at this structural level. Ethno-linguistic and religious conflict are more potent in the east than in the west, but I am struck by the Cold War absurdity of putting Finland and Greece into one “Western Europe.” The ethnic questions so pronounced in many eastern European countries are also visible in the west, and I suspect that similar dynamics may be at work in the west especially as ethno-regional identities become more salient in the context of the economic crisis and mobilized by (possibly failed) referenda on independence.

Whitefield: Just a further word in defence of CEE parties here. I mentioned earlier that parties in West and East seem equally capable of representing voters at least in their programmatic offerings. Actually, there is one increasingly important issue – European integration – on which mainstream parties in the East may outperform their Western counterparts in representational terms. As the European issue has loomed larger and citizens have over the past years since the onset of the financial crisis become increasingly Euro-sceptic, it is interesting that mainstream parties in the West have not adjusted their stances on integration to reflect that Euro-scepticism nor have they increased the salience of Europe in their electoral appeals, in fact quite the opposite. This means that almost all of the representational strain of rising Euro-scepticism in the West has been taken up by extreme parties – and these are often parties that are not just extreme on integration but on other issues also. But, as Robert and I show in a recent paper, the representational strain is being taken up much more by mainstream parties in the East, which may mean that there is less of an opening for extreme parties and may also mean that the rise of anti-politics associated with representational failure by mainstream parties may be mitigated in the East. Why are post-Communist parties more willing to move on integration issues than their Western counterparts? Because, in our view, the issue of Europe is bound up on the main axis of political competition rather than, as in the West, sitting orthogonally to it. In the East, mainstream parties always competed on Europe. In the West, mainstream parties don’t compete on it, don’t own the issue, and don’t want to talk about it, leaving it to other parties to take up. That is quite dangerous in my view.

Next Steps

Deegan-Krause: So in light of all of the discussion to this point, what is it that our field needs most? Where should we be putting our attention?

Haughton: Put simply, I am particularly interested in the success and failure of parties at the ballot box: why some succeed, why some have lasting success, some merely fleeting success and why other parties fail to persuade voters to support them. To that end, if time and resources permitted I’d want to conduct large-scale comparative research to work out why voters cast the ballots the way they did (interviewing, focus groups etc. plus polling) over a series of electoral cycles. Much of what we have to do is make educated guesses based on opinion polling and surveys which are often not easily comparable or in a form which makes satisfactory comparison possible. We are left to infer from these statistics which may be accurate, but ultimately we don’t know. Beyond that, I’d love to be able to visit every branch of every party in the region to talk to the activists and party workers.

Rovny: I would like to see a research agenda should focus on the historical state-building elites, on the formation of political camps, and on their social bases of support. Provocatively, such an agenda should question whether these historical factors may ‘return’ to frame eastern European politics as the experience of communism recedes into the past.

Deegan-Krause: I think we need to work in Eastern Europe on the general topic of alignment-dealignment-realignment and whether what we are seeing is a general reduction in the socio-demographic underpinnings of political attitudes and voting behavior and to what extent there is (as Kitchelt, Kriesi and others have suggested) a shift to socio-demographic underpinnings that have not traditionally been the subject of inquiry (sector, professional group). There is a related question of method and data with regard to these questions of things that parties fight about. The range of sources is great: what experts say about where parties stand (according to various standards, pioneered the Rohrschnedier and Whitefield studies and the North Carolina research, both represented in this discussion), what elites say (to scholars in surveys, or with their votes—the core of the work by Monika Nalepka and Royce Carroll–or with their speeches or with their manifestos), what voters say about parties , what voters of parties believe (according to focus groups, according to surveys). In some cases disagreements about what is going on in countries rests on these different indicators point in different directions. I’m wondering to what extent we can integrate these perspectives and what kinds of additional we need and what computational methods might allow us to find some common positions for parties on multiple dimensions. I’d also like to see us develop much more sophisticated measures of party change to replace our binary determination of “successor” v. “not-successor” and therefore allow improved understanding of the nuances of supply side shifts and voter decisions that appear to be dealignment but may in reflect voters following their preferred party leaders from one new party to another.

It may also be worth noting that as part of another project we have conducted an informal poll of over 100 scholars of party systems in regions across the world and found a wide range of topics that experts think we should be studying:

- Questions of intra-party relationship gathered the attention of 30% of all the scholars involved, but the sub-sets split evenly and widely along directions such as organization and party finance, leadership selection, party-parliamentary relationships, party membership and party life cycle. In comparison to others, scholars of Eastern Europeans tended to emphasize organization and finance rather than membership and factions.

- An almost equal share—27%—mentioned relationships between parties and their voters. A plurality of these comments focused on voting behavior, but significant shares also went to cleavages and turnout and a few others emphasized a broad range of other topics including clientilism, representation, party communication strategies and dealignment. These voting behavior questions were far more popular among those who study Eastern Europe.

- While few scholars of other regions focused on specific party types, 15% of the scholars of Eastern Europe found these extremely interesting. Of these just under half mentioned “new parties” and a significant number mentioned populist parties.

- The position of parties in the broader context of domestic and international political systems also attracted about 15%. As might be expected, those who study Eastern Europe were more interested in the broad process of party Europeanization than scholars from other regions, but they were (again, perhaps indicative of the region) overall less interested in interest groups and policy outcomes.

- About 10% of the suggestions concerned relationships between parties. Most of these mentioned the study of party positions and dimensions of competition but a few mentioned coalition formation and volatility. The scores for those who study Eastern Europe were in line with these figures in general but considerably higher on the question of volatility.

Useful Guides

As we are moving forward with agendas such as these, what scholarly resources are the most useful? Which ones shape your own work? Let’s start with research on parties as institutions in their own right:

Haughton: I am extremely fond of Redeeming the Communist Past, which is full of significant theoretical and empirical contributions. The question for us now is how to take this kind of work into the second and third post-communist decade. We’ve recently been compelled by Margit Tavits’s Post-Communist Democracies and Party Organization, as well as by Allan Sikk’s works on new parties and “newness” as a quality with its own right

Rovny:Also, I very much like the Allan’s work with Sean Hanley on new anti-establishment parties.

Haughton: Ingrid van Biezen has really helped broaden our understanding about patterns of party change (are parties the way they are because of when they were born, how old they are, or the period in which they are operating) and Andre Krouwel has done helpful work on party typologies for the new century. And recent work by Mainwaring, Gervasoni and Espana and Powell and Tucker have both independently started to enrich our understanding of volatility by looking at the role of system entrances and exits.

Deegan-Krause: What about the broader level of party systems and voting. What are your strongest influences?

Whitefield: as we study the questions of what voters want from parties, we would recommend Dalton’s recent piece on partisan learning in new democracies, Barnes et al’s work on the Spanish transition; and Brader and Tucker’s recent work [on].

Rovny: I would add Stephen’s and Robert’s The Strain of Representation and the string of related articles.

Haughton: And along with The Strain of Representation (and the surveys that book and other work of Stephen and Robert is based on) we would add the many articles from the Chapel Hill expert surveys (in which Jan has played a major role)

Rovny: I think the overall contribution here is to help to resolve a long-standing debate in the field, through a multiplicity of similar pointing to the relatively stable ideological nature of political competition in Eastern Europe, underpinned by social divides and individual preferences. Other recent works, such as those by Margit Tavits have echoed these conclusions.

Deegan-Krause: And while they are not always in perfect agreement, the similarities of their findings on party positioning and, especially, the role of issue salience help us map the electoral environments we are dealing with and understand why parties compete and form coalitions as they do. There is a lot of work to be done and other kinds of measures to be integrated but both of these big studies are an important first start. What sources do you find yourself relying on when looking upstream to the sources of political parties and party systems?

Whitefield: When I look to the citizen-party relationship, I often look to the issues raised by Robert Michels’ Political Parties, John Aldrich’s study Why Parties, Henry Hale’s “Why Not Parties,” and Dalton, Farrell and McAllister’s “Political Parties and Democratic Linkage.”

Deegan-Krause: On the role of legacies, I’d highlight Kitschelt’s work on divergent paths of post-communist transitions as well as his earlier work on cleavages and connections between citizens, parties and outcomes.

Rovny: In a similar vein, I find the works by Grigore Pop-Eleches and Joshua Tucker on legacies crucial for our deeper understanding of what it actually is that shapes party conflict in the region.

Deegan-Krause: And looking downstream to the consequences of particular party configurations and outcomes.

Whitefield: On the link to the quality of democracy, I really like Thomassen’s and van Biezen’s work which connect empirical questions about parties to a concern with good governance.

Haughton: I also think the state-building literature has been a valuable contribution to the study of the effects of party politics Conor O’Dwyer’s Runaway Statebuilding, the Venelin Ganev’s Stealing the State and Anna Grzymala-Busse’s Rebuliding Leviathan.

Deegan-Krause: Andrew Roberts’ The Quality of Democracy in Eastern Europe also deals well with the consequences of party competition in particular policy realms.

We asked this same question in our survey of party scholars, and there was considerable agreement on the most important works in the field. Our respondents include nearly all of the works we mentioned here along with several others. By far the most frequently mentioned scholar of parties among our experts is Peter Mair, both alone and in cooperation with Dick Katz

Also receiving multiple mentions the list among scholars of the region are

- Bonnie Meguid’s work on niche parties and

- Cas Mudde work on populism and the radical right

- Fernado Casal Bertoa and Zsolt Enyedi’s work on cleavages,

- the work of Hanspeter Kriesi and his team of scholars on issue dimensions and globalization,

The list also included the classic works by Lipset and Rokkan, Sartori, Bartolini and Mair, Lijphart, Pannebianco, Scarrow, Knutsen and Scarbrough and Cox.

Lists of scholars who work on other political parties in other regions echo this list of classics along with some of the other works listed here including Mair, Kriesi and Meguid. Here is of the books and articles most commonly cited by scholars of the region is available. Another list including all 100+ books and articles citied by scholars in the survey is available below.

“Adams, James (2005) A Unified Theory of Party Competition. Cambridge University Press

A Cross-National Analysis Integrating Spatial and Behavioral Factors”

Adams, Ezrow, and Somer-Topcu “”Is Anybody Listening”” (2011).

Albright, Jeremy (2010) The multidimensional nature of party competition in Party Politics have been of great interest.

Baumgartner, Frank R., and Bryan D. Jones. 1993. Agendas and Instability in American Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Benoit Ken and Michael Laver – Party Policy in Modern Democracies (2006)

Berman Sheri “”The Primacy of Politics”” (2006).”

Bevan, Shaun, and Will Jennings. 2014. ”Representation, Agendas and Institutions”. European Journal of Political Research 53(1): 37-56.

Bevan, Shaun, Peter John, and Will Jennings. 2011. «Keeping party programmes on track: the transmission of the policy agendas of executive speeches to legislative outputs in the United Kingdom». European Political Science Review: 1–23.

Birch, Sarah (2003), Electoral systems and political transformation in post-communist Europe. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Budge, Ian, and Richard I. Hofferbert. 1990. “Mandates and Policy Outputs: U.S. Party Platforms and Federal Expenditures.” The American Political Science Review 84(1): 111-131.

Budge, Ian, Hans-Dieter Klingeman, Andrea Volkens, Judith Bara, and Eric Tanenbaum. 2001. Mapping Policy Preferences. Estimates for Parties, Electors, and Governments, 1945-1998. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Budge, Ian, Hans-Dieter Klingemann, Andrea Volkens, Judith Bara, et al. 2001. Mapping Policy Preferences: Estimates for Parties, Electors, and Governments 1945-1998. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Caplan, Bryan (2007) The Myth of the Rational Voter. Princeton University Press.

Capoccia, Giovanni and Daniel Ziblatt (2010), ‘The Historical Turn in Democratisation Studies: A New Research Agenda for Europe and Beyond, Comparative Political Studies, p.931-968.

Carey, John M. (2008) Legislative Voting and Accountability. Cambridge University Press.

Carty Kenneth (2004) Parties as Franchise Systems

Caul Kittilson, Miki (2006) Challenging Parties, Changing Parliaments. Women and Elected Office in Contemporary Western Europe. Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University Press.

Chandra, Why Ethnic Parties Succeed;

Chhibber, Pradeep and Ken Kollman (2004) The Formation of National Party Systems. Federalism and Party System Competition in Canada, Great Britain, India and the United States. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Crotty (eds) Handbook of Party Politics, London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi: Sage, pp. 204–27.

Crouch, C. (2004) Post-Democracy. Cambridge: Polity.

Dalton “Political Parties and Democratic Linkage: How Parties Organize Democracy by Russell J. Dalton, David M. Farrell and Ian McAllister

Dalton and Wattenberg, Parties without Partisans

Dalton, R., D. Farrell en I. McAllister (2011) Political Parties and Democratic Linkage; How Parties Organize Democracy, Oxford: Oxford Unversity Press

Dalton, R.J. and Wattenberg, M.P. (eds) (2000) Parties without Partisans: Political Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies. NY: Oxford University Press.

Dalton, Russell J. (2008) ‘The Quantity and the Quality of Party Systems: Party System Polarisation, Its Measurement, and Its Consequences’, Comparative Political Studies, 41, pp.899-920

Dan Posner, Institutions and Ethnic Politics in Africa;

De Vries, Catherine and Sara B. Hobolt (2012) ‘When Dimensions Collide: The Electoral Success of Issue Entrepreneurs’, European Union Politics, 13(2) 246-268.

Eijk and Franklin 2009

Erikson, R.S., MacKuen, M.B. & Stimson, J.A. (2002). The macro polity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Evans G. & De Graaf, N.D. Political Choice Matters: Explaining the strength of class and religious cleavages in cross-national perspective, Oxford University Press, 2013.”

Fiorina, M. (1981). Retrospective voting in American elections. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Franklin, Voter Turnout and the Dynamics of Electoral Competition in Established Democracies since 1945 by Mark N. Franklin

Gallagher, M. and M. Marsh. (1988). Candidate selection in comparative perspective. Londres: Sage Publications.

Green-Pedersen, Christoffer, and Peter B. Mortensen. 2010. ”Who sets the agenda and who responds to it in the Danish parliament? A new model of issue competition and agenda-setting”. European Journal of Political Research 49(2): 257–81.

Halikiopoulou, D., Mock, S. and Vasilopoulou, S. (2013) The civic zeitgeist: nationalism and liberal values in the European radical right. Nations and Nationalism, 19 (1). pp. 107-127

Heidar, K. (2007) ‘What Would be Nice to Know about Party Members in European Democracies’, ECPR Joint Sessions, Helsinki, 7-12 May 2007.

Hibbing, John, and Theiss-Morse, Elizabeth. (2002). Stealth Democracy. Americans’ Beliefs About How Government Should Work. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hobolt, Sara B., Jae-Jae Spoon and James Tilley (2009) ‘A vote against Europe? Explaining defection at the 1999 and 2004 European Parliament elections’, British Journal of Political Science , 39(1): 93-115.

Hobolt, Sara Binzer, and Robert Klemmensen. 2008. ”Government responsiveness and political competition in comparative perspective”. Comparative Political Studies 41(3): 309–37.

Hofferbert, Richard I., and Ian Budge. 1992. “The Party Mandate and the Westminster Model: Election Programmes and Government Spending in Britain, 1948-85.” British Journal of Political Science 22(2): 151-182.

Hooghe 2006. Party Ideology and European Integration: An East/West: Different Structure, Same Causality, with Liesbet Hooghe, Moira Nelson and Erica Edwards. Comparative Political Studies 39(2), 155-75.

Jones, Bryan D., and Frank R. Baumgartner. 2004. ”Representation and Agenda Setting”. Policy Studies Journal 32(1): 24.

Jones, Bryan D., and Frank R. Baumgartner. 2005. The Politics of Attention: How Government Prioritizes Problems. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press.

Kahneman Daniel and

Kam, C. D., & Palmer, C. L. (2008). Reconsidering the Effects of Education on Political Participation. The Journal of Politics, 70(03), 612–631.

Katz and Kolodny (1994)

Katz, R. y P. Mair. 1995. “Changing models of party organization and party democracy: the cartel party”, Party Politics 1:1-28.

Katz, R.S. (2005) ‘The Internal Life of Parties’, in K.R. Luther, F. Müller-Rommell (eds) Political Parties in the New Europe. Political and Analytical Challenges. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kedar, orit book”

Klingemann, The Comparative Study of Electoral Systems by Hans-Dieter Klingemann”

Kitschelt 2000, CPS: “”Linkages between citizens and politicians in democratic politics.””

Kitschelt Herbert “”The Transformation of European Social Democracy”” (1994).

Kitschelt, H. (2000) ‘Linkages between citizens and politicians in democratic polities’, Comparative Political Studies, 33 (6–7): 845–879.

Kitschelt, H. (2007) Growth and persistence of the radical right in postindustrial democracies: Advances and challenges in comparative Research (West European Politics)

Klingemann, H. D, R. I Hofferbert, I. Budge, e H. Keman. 1994. Parties, policies, and democracy. Westview Pr.

Knutsen, O. and Scarbrough, E. (1995) ‘Cleavage politics’, in J. van Deth and E. Scarbrough (eds) The Impact of Values, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 492–523.

Laver, Michael, and Budge, Ian (Eds.). (1992). Party policy and government coalitions. New York: St. Martin’s.

Laver, Michael, e Kenneth A. Shepsle. 1996. Making and breaking governments: Cabinets and legislatures in parliamentary democracies. Cambridge University Press.

LEIRAS, Marcelo (2005) Todos los caballos del rey: la integración de los partidos y el gobierno democrático de la Argentina, 1995-2003. Buenos Aires: Prometeo.”

Lijphart Patterns of Democracy (latest edition)

Lovenduski, Joni (2005) Feminizing Politics. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Lovenduski, Joni and Pippa Norris (1993) Gender and Party Politics. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Luna Juan Pablo, 2014, Segmented Representation, Oxford.

Mair, P. (2006a) Ruling the Void? The Hollowing of Western Democracy. New Left Review, 42. 25-51

Mair, Peter (2008) The Challenge to Party Government, West European Politics, 31:1-2, 211-234

Mair, Peter, and Jacques Thomassen. “”Political representation and government in the European Union.”” Journal of European Public Policy 17.1 (2010): 20-35.

Mair, Ruling the Void (or his earlier The West European Party System)

Manin, B. (1997) The Principles of Representative Government, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

McDonald, Michael D., and Ian Budge. 2005. Elections, Parties, Democracy: Conferring the Median Mandate. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Meguid, Party Competition Between Unequals

Morgenstern and Potthoff, Electoral Studies, 2005: “”The Components of Elections.””

Moser and Scheiner, Electoral Systems and Political Context;

Mudde, Cas (2007) Populist Radical Right in Europe (CUP)

Müller and Strom, Policy, Office or Votes,

Panebianco (1988)

Petrocik, J. R. 1996. «Issue ownership in presidential elections, with a 1980 case study». American Journal of Political Science: 825–50.

Plasser, Fritz and Gunda Plasser (2002), Global Political Campaigning. A Worldwide Analysis of Campaign Professionals and Their Practices, Westport CT: Praeger.

Powell and Tucker on improving our understanding of measuring volatility.

Przeworski’s entire work.

Randall, Vicky and Lars Svasand (2002) ‘Party Institutionalisation in New Democracies’ Party Politics, 8:5, pp.5-29.

Riker, W.H. (1962) The Theory of Political Coalitions. New Haven: Yale University Press

Rothstein, Bo The Quality of Government

Rydgren, Jens (ed.) Class Politics and the Radical right (Routledge)

Samuels and Shugart, Presidents, Parties, and Prime Ministers;

Sartori, Giovanni. 1976. Parties and Party Systems: a Theoretical Framework. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Scarrow (2007)

Schofield Norman and Itai Sened, Multiparty Democracy: Elections and Legislative Politics

Sigelman, Lee, and Emmett H. Buell. 2004. “Avoidance or Engagement? Issue Convergence in U.S. Presidential Campaigns, 1960–2000.” American Journal of Political Science 48(4): 650–61.

Simpser, Why Governments and Parties Manipulate Elections: Theory, Practice, and Implications by Alberto Simpser

Sniderman, Paul, and Hagendoorn, Louk. (2007). When Ways of Life Collide: Multiculturalism and its Discontents in the Netherlands. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.”

Soroka, S.N., e C. Wlezien. 2010. Degrees of democracy. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Stegmueller’s POQ article on individual-level partisan dynamics.

Stimson, J.A., MacKuen, M.B. and Erikson, R.S. (1995). “Dynamic representation”. American Political Science Review 89: 543–565

Strøm, K., W.C. Müller and T. Bergman (eds) (2008), Coalition Bargaining: The Democratic Life Cycle in Western Europe, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Strøm, Kaare, and Wolfgang C. Müller. 1999. «The keys to togetherness: Coalition agreements in parliamentary democracies». The Journal of Legislative Studies 5(3-4): 255–82.

Strøm, Kaare. 2000. “Delegation and Accountability in Parliamentary Democracies.” European Journal of Political Research 37(3): 261-289.

Sulkin, T. 2005. Issue politics in Congress. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ Press.

Thomassen The European Voter (Jaqcues Thomassen ed)

Tsebelis, George. 2002. Veto Players: How Political Institutions Work. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Tversky, Amos. (1988). Contrasting Rational and Psychological Analyses of Political Choice. American Political Science Review.

van Biezen (2004)

Van der Brug, Wouter, and Joost Van Spanje. “”Immigration, Europe and the ‘new’cultural dimension.”” European Journal of Political Research 48.3 (2009): 309-334.

Van der Meer, Tom, et al. “”Bounded volatility in the Dutch electoral battlefield: A panel study on the structure of changing vote intentions in the Netherlands during 2006–2010.”” Acta Politica 47.4 (2012): 333-355.

Warwick, Paul V. 2001. “Coalition Policy in Parliamentary Democracies Who Gets How Much and Why”. Comparative Political Studies 34(10): 1212–36.

Warwick, Paul V. 2011. “Voters, Parties, and Declared Government Policy.” Comparative Political Studies 44(12): 1675–99.”

Webb, Party Politics in New Democracies”

Young, L. (2013) ‘Party Members and Intra-Party Democracy’ in W.P. Cross and R.S. Katz The Challenges of Intra-Party Democracy, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

East European Politics and Societies Special Section: Political Parties in Eastern Europe

East European Politics and Societies Special Section: Political Parties in Eastern Europe